"You Won't Come Back Alive"

In 1943, NTM’s first team of missionaries went to Bolivia to seek out people groups who had never heard the gospel and to establish a church among them. They succeeded — at great cost.

Little was known about the Ayoré people, and what was known would not put your mind at ease. Their nomadic way of life complicated every effort at making a friendly contact — if a friendly contact were even possible.

“You won’t come back alive,” the missionaries were warned. But this did not deter them.

Others asked them, “Why go out there and risk your lives?”

The answer was simple: “It is because the glorious name of Jesus is not known here, and must be made known at any cost, … that we are going,” Cecil Dye explained. “I don’t believe we care so much whether this expedition is a failure so far as our lives are concerned, but we want God to get the most possible glory from everything that happens.”

And so they went.

After months of arduous labor, cutting their way through the dense jungle and suffering physical injuries and diseases in the process, they reached a small stream. It was November of 1943, and from here on they anticipated contact with the Ayorés at any time. Clyde Collins and Wally Wright returned to Robore with the donkeys and excess supplies while the other five men prepared to continue on: Dave Bacon, Bob Dye, Cecil Dye, George Hosbach and Eldon Hunter.

Cecil’s final words to Clyde and Wally were, “If you don’t hear anything inside a month, you can come and make a search for us.”

A month passed. A long month. And no word.

THE UNKNOWN

Search parties went out. They found items belonging to the men — but no men.

“Just below the surface … was the question, ‘Are our husbands still alive?’” wrote Jean, Bob Dye’s wife. “There was nothing we could do but wait. ... It would be good to know. The days dragged on. … The waiting became unbearable.”

Days turned into weeks, months and years before the truth would be known. But the remaining missionaries were determined to win the souls of the Ayorés to Christ. Their loss was great, but their outlook unchanged. They picked up the torch laid down by the five men.

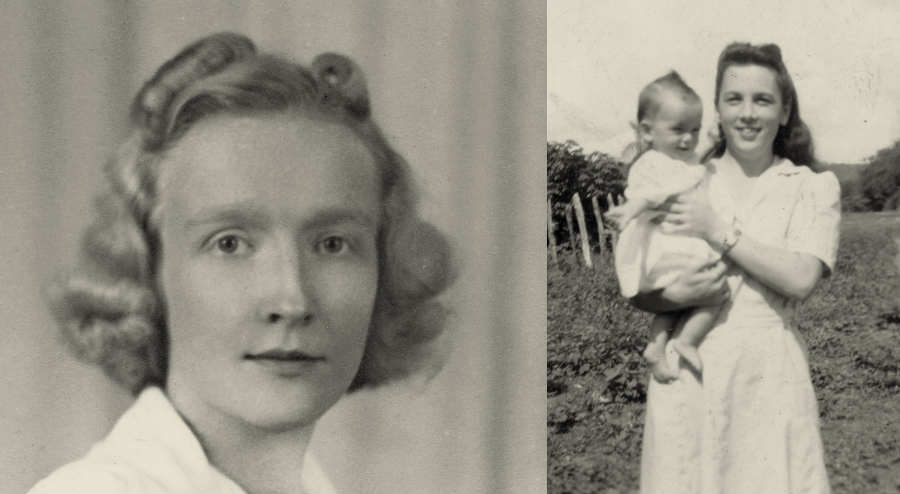

Left - Jean Dye Johnson; Right - Audrey Bacon with baby Avis

Left - Jean Dye Johnson; Right - Audrey Bacon with baby Avis

DESCENDANTS OF WHITE BUTTERFLY

It would be four long years of unsuccessful attempts before the first friendly contact was made on August 12, 1947.

“That one who gave us things … the very white one with the very white hair, where does she come from?” the Ayorés asked amongst themselves. “Who are her ancestors?”

Ejene, one of the Ayoré men, had made up his mind about her. “She is Corabe’s descendent,” he answered them with an air of authority. “She and her companions are the offspring of White Butterfly.”

This brought about a stunned silence. In Ayoré folklore, there was a fair-skinned Ayoré named White Butterfly who was held in high esteem. To them, she was the essence of loveliness in body and spirit. Her fair skin stood out in contrast to her bobbed black hair, and though she and her friends prettied their bodies with charcoal designs, White Butterfly never left herself painted for long. She didn’t particularly like getting painted up. And why did it matter? She was the most sought-after bachelorette in the tribe with or without it.

Dorothy Dye traveling to another village

Dorothy Dye traveling to another village

Every eligible young man in her tribe pled with White Butterfly to choose him. But as was the tradition among her people, the choice was White Butterfly’s — and she wasn’t quite ready to settle down and get married.

As fights broke out among her would-be suitors, White Butterfly felt pressured to make a choice. But how could she when she didn’t know “how her insides went”? How should she choose a husband?

And then it came to her. She climbed to the top of a slippery tree in the jungle. And like a night owl calls for its mate, she called out a challenge through a friend to her would-be suitors.

Soon the village was buzzing with White Butterfly’s unorthodox manner in choosing a husband: “Corabe will be the wife of the one who climbs the slippery tree and reaches her first!”

Young warriors searched the jungles, peering through the foliage to the tops of each tree in search of the desirable White Butterfly. And then they found her.

One after another, the young warriors attempted to climb the slippery tree. The crowd below swelled in numbers as relatives cheered on the would-be bridegrooms. But one after another they failed to reach the top. White Butterfly alternately taunted them — and then cheered them on.

“Remember, whoever reaches the top first will be my husband. It doesn’t matter whether he is young, an inexperienced hunter or even if he’s not handsome. Whoever reaches me first shall have me!”

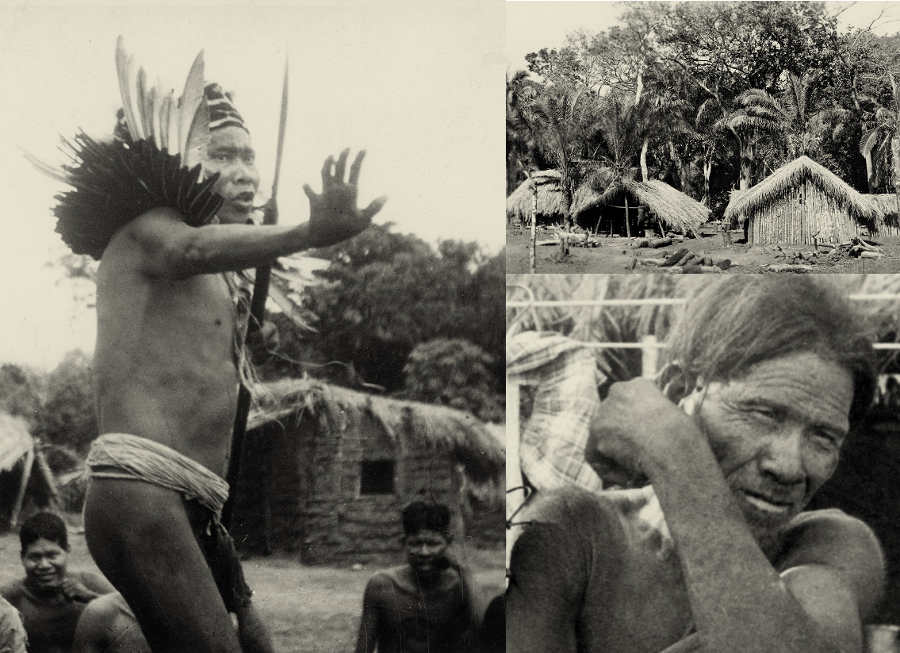

Left - Ayoré Warrior; Right - Upoide, a transformed life

Left - Ayoré Warrior; Right - Upoide, a transformed life

And then Little Lizard pushed his way through the crowd. He was inexperienced, short, squat and far from handsome. But he didn’t let that stop him. White Butterfly had said, “Whoever reaches me first shall have me.” That included him.

“Get out of my way so I can have a chance to shinny up that tree!” he cried out. “I think I am going to make it.”

“You make it?” the crowd jeered. “Where all the valiant ones fail, what makes you think you’ll succeed?” But they made way for him to approach the tree.

Little Lizard began to climb. Slowly. Steadily. But with a firm grip.

The jeering faded as the crowd watched him disappear into the upper branches.

“He made it!” the crowd cried. And true to her word, White Butterfly claimed him as her husband.

But that was not the end of it. Many of her would-be bridegrooms were consumed with jealousy. They began to continually find fault with Little Lizard, which in Ayoré culture was a threat. And threats often led to killings.

Fleeing was their only option. They fled north, farther north than any other Ayoré had ever ventured, and that was the last they were seen.

And now here were people from the north with fair skin, fair-skinned like their ancestor White Butterfly. Did it not stand to reason that these fair-skinned people could be descendants of White Butterfly?

God used this thought process to instill in the Ayorés a desire to become friends with the missionaries -- and eventually brothers and sisters in Christ.

BUT WHAT ABOUT OUR MEN?

But one question always remained: What had happened to the five men?

It wasn’t until 1950, after a friendly contact was established with a neighboring clan, that the truth came out. One of the men had been there. He knew what had happened. And he was willing to talk.

He shared that though the Ayorés were alarmed when the five white men walked into their village, they didn’t shoot on sight. But they did keep a vigilant eye on the men placing gifts in the center of the clearing.

At first, all went well. Gifts were a good thing. But an hour into the contact, trouble brewed. One of the warriors got upset, believing he deserved a bigger gift. And out of that greed, the five men were killed.

Later, when the chief returned and learned what had happened, he was upset with the warriors. “You shouldn’t have killed them,” he told them. “I would not have killed them.”

He noticed what his warriors had missed. The white men had not brought guns. They had come in peace.

But it was too late. The men were dead. They were buried in an Ayoré garden.

BEAUTY FROM THE ASHES

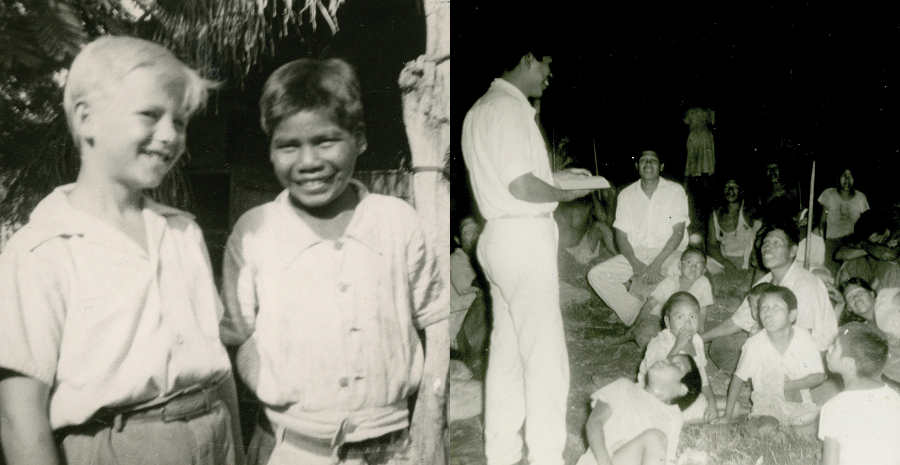

Left - Cecil Dye's son, Paul, with his Ayoré friend Jomone; Right - Ayoré believer, Ecarai, sharing the gospel with fellow tribesmen

Left - Cecil Dye's son, Paul, with his Ayoré friend Jomone; Right - Ayoré believer, Ecarai, sharing the gospel with fellow tribesmen

Do you remember what Cecil wrote before facing martyrdom? “I don’t believe we care so much whether this expedition is a failure so far as our lives are concerned, but we want God to get the most possible glory from everything that happens.”

And God did. God brought beauty from the ashes. An Ayoré church was born. And eventually, the family of those who’d killed the first five men became part of the family of God.

It was a bittersweet moment when these relatives, accepting the blame as their own, told Audrey Bacon, “We’re sorry we killed your husband. We didn’t know better.” And then they waited for a response.

Can you imagine being Audrey? How does one respond to that? In and of ourselves, it would be hard to come up with a good response. But God bringing beauty from the ashes wasn’t limited to the Ayorés. He turned the ashes of grief to something beautiful, to hearts focused on Him.

“It was worth my husband’s death to see you come to know Jesus Christ,” Audrey reassured them, speaking from the heart for each of the widows.

It was worth it. Do you hear the sacrifice behind those words? Do you hear the challenge behind those words? What is it worth to us, today, to see others reached for Christ?